Content warning: war

Please note: As with anything I write (with the exception of historical or scientific evidence and data), this is a work of my own experience and impressions. It’s important to note that the family I refer to in this essay includes dozens of individuals, each with their own experiences.

🪐🪐🪐

TRANSCRIPT:

DEAR GRANDMA & GRANDPA~

Challenging our family unit used to be disrespectful, an act of nullifying our very selves. Family, above all, was most important, and as such it could never EVER be questioned. We were taught that love and legacy were synonymous with unquestioned loyalty.

Sometimes it feels like people in our family love the word ~LEGACY~

In prayers, in bios, in obituaries, we’d put it on a cake if we could. But what does it actually mean?

leg·a·cy — /ˈleɡəsē/ — noun

something passed down to a descendant, most likely an asset or monetary gift

something transmitted by or received from an ancestor or predecessor from the past

FOOD & TEARS~

Growing up, we were occasionally deposited at your place for supervision. The condo is packed with flashes of memory — a cockatiel in the garage, stiff bazooka bubble gum you pulled from behind my ear, my cousin pulling my hair and biting me when nobody was looking, you walking around with plastic bags tied around your slippers, cherry almond soap, being forced to face the backside of the couch for a nap while Grandma, you did fun shit like snacking on fruit slices and watching Filipino soaps. It was a pattern, facing the other direction instead of the freedom to embrace the culture. Tagalog spoken as a secret language between not Lola and Lolo, but Grandma and Grandpa. The tangible bits of the culture withheld, the mystifying bits seeping into us.

WIPE YOUR PEET! you’d shriek. You’d shriek at Grandpa as he drove. You’d shriek at the fake rubber piece of poo Uncle Tony placed on the kitchen floor. You’d give us a half stick of gum. You’d wipe the floor with your foot over a square of Bounty while pushing air through your teeth.

Grandpa, you had this regimented way of feeding us. Remember the Christmas Eve when you spoon fed me so much that I threw up into a huge green bowl? Spoon feeding us was part of your love language. We were stuffed with picadillo, heaps of rice, adobo, sweet spaghetti, pancit, scrambled eggs and banana pancakes slathered in Mrs. Butterworth syrup from the commissary before receiving branded cookies: Keebler Elves or SnackWells. If we were lucky we were given buttered pandesal. A weathered Tupperware cup of milk sat waiting to wash down the whole shebang at the end.

What I would now give to sit under the fluorescents while you bobbed around the kitchen in a sweatsuit. Afterward you’d inspect my dish, and if it wasn’t completely wiped (squeegee style) then there’d be work to do. In a seemingly empty bowl you would somehow find 5 additional bites. Disobedience would’ve never occurred to me. Finishing food entirely was as crucial as breathing.

On one visit, when I was 7 or 8, my baby brother had been inconsolable. One of my aunts placed me in a bedroom and told me to lie back.

"You're his sister," she said. "You should take care of him."

She plopped him on top of me and shut me in.

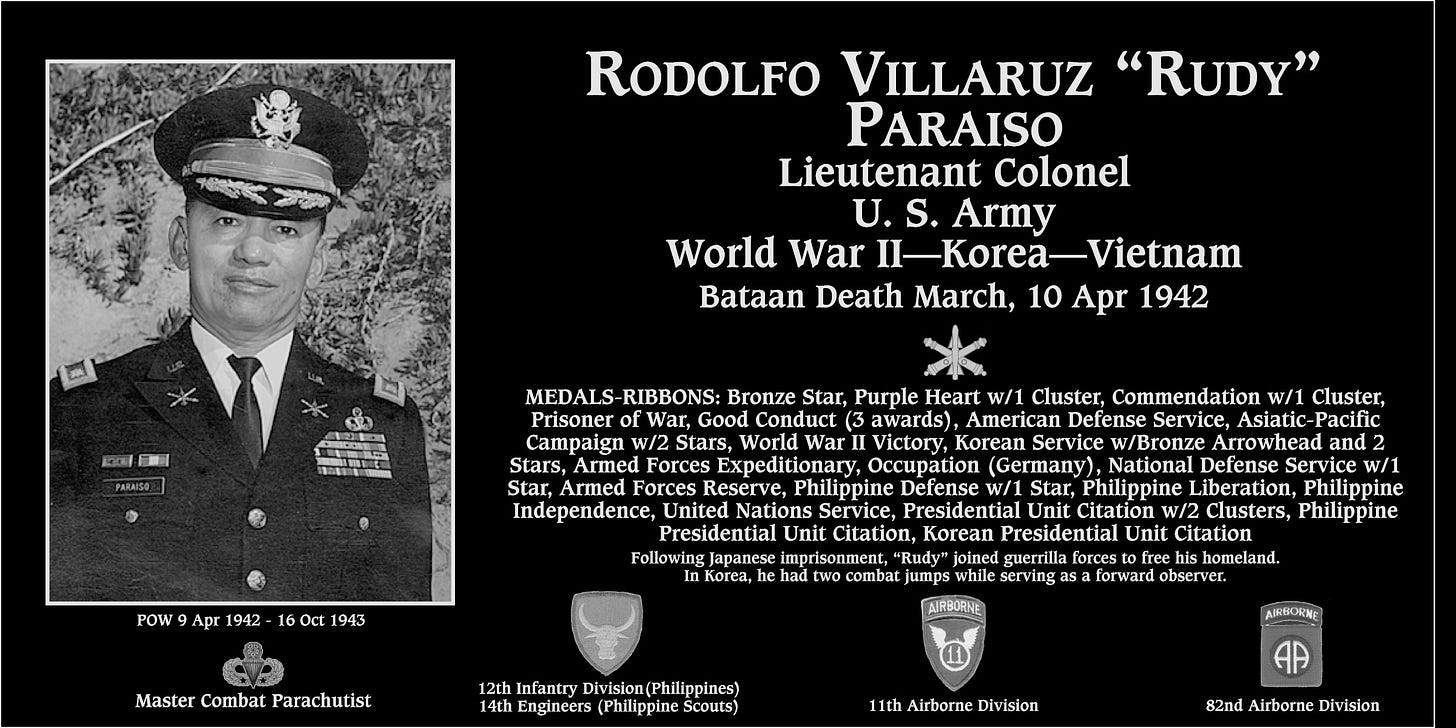

He wailed and wailed, the chunky wet blob of him heavy and real, for what felt like hours. Sunlight crowded behind the plastic blinds, creating shadows on the opposite wall. I stared at your medals in their case, the rainbow of prestigious ribbons, instinctively distracting myself. I thought of you fighting in the war. Certainly there was zero room to complain (“I’ll give you something to cry about!” a regular adage at home). Auntie’s logic was sound, he was my brother.

When my own tears welled, my first reaction was fear. I had no excuse for crying, and the idea of being discovered filled me with shame. Eventually I reasoned that if I was silent, nobody would barge in. We cried together. You had no indication of these oceans stirring within me, and I took it as my responsibility to conceal them.

WAR~

Once, before a comedy performance, a friend’s parent asked me, “How are you feeling about the upcoming performance?” I thought, wait wait wait. Is this was his childhood was like? Somebody asking him how he felt?

I tried to imagine you asking my dad this. Why would you? I tried to imagine my parents asking me this. I imagined you, asking yourself this. I thought of my father, so unnerved by his own feelings that he demonized mine.

The pamphlet for your celebration of life focused heavily on “God” and accolades, but I know there was more to you than that because there’s more to everyone than that. If only I could time travel back to ask you myself without being so starstruck. With 25 first cousins in the family, we each had a different relationship to you. While some cousins had a closeness with you, a favor that I envied, mine felt like that scene in Toy Story where the toys are conversing from the upstairs windows of neighboring houses. Yelling to be heard across a divide, all my words tumbling down into it.

Evidently, honoring you was valued higher than knowing you. Few seemed to value knowing, when everyone valued honor. Honor was praying, giving you a good Christmas gift, procreating, your grandkids exceeding expectations. I didn’t know how to honor you that way. Did there ever exist a way of honoring and knowing simultaneously?

Grandpa, what did it feel like being a prisoner of war in the Bataan Death March? How many times did you think you would die? What did it feel like being stabbed with a goddamn bayonet? What did it feel like the day you were liberated? Did you have survivor’s guilt? HOW did you go from that total nightmare to joining Guerrilla forces to free the Philippines? HOW did you go from that to the Korean war? Was it simply career, was it duty, was it guilt, was it numbness? Was it avoiding the hollowness of a civilian’s life after the carnage you’d witnessed? If ever the war came up at all, you’d weep so quietly. Did you ever want to weep at the top of your lungs? Did you even want to be on the sky high pedestal you were on?

The ramifications of your sacrifices were barely spoken but always felt. Your black belt in karate, your black belt in judo. Every stubborn pushup you did into your 80’s, every family prayer you prompted, every thwack of a racquetball, every story of you coming home from the officer’s club swaying, every new baby you held, every military ribbon, your combat jumps, your bronze star for valor, your purple heart, your stillness. I used to dream about walking beside you in the death march, offering water and spooning food. Shielding you from the scorching sun. The way you wore your Elite 82nd Airborne hat, perched atop your head, balancing. Your face on your 100th birthday as you sat before the candles in uniform, clutching grandma’s hand and staring into the flames. What were you thinking in that very moment?

Grandma, did you miss your half family back in Manila? Did you question why it was your mother, your family, that your polygamous father chose to bring to America? Was your religion, your focus on the superficial, a replacement for the perilous work of processing, or yet another aspect of it? The grueling war, running barefoot from home when your village was bombed, your feet becoming bloodied, your father’s concubines, the violent adult death of your firstborn son? Did you believe that the work needed to be done in secret? Were you holding your breath? Who were you, really? I’m desperate for more than the handful of rote stories and will never know. I could only feel the impressions of your authority which filled the corners with every visit to your impeccably kept condo with plastic covering the dining table and wooden fruit in a bowl. I used to imagine an aerial view of you fleeing the bombing. I so wished I could give you shoes to wear, that I could dive down in my helicopter and scoop you inside.

Before my move to Los Angeles, your blessing was “Yes, you’re pretty enough to be an actress.” I could not articulate why that stung me, it wasn’t a language we spoke. Your often used phrase is tattooed on my wrist in your handwriting: ay nako. It’s me saying, well shit. I’m so sorry I didn’t try harder to know you better than I did.

TALK LESS, BABY MORE~

Years ago during a prayer, a megaphone was handed to you, Grandpa. We used to chant, “SPEECH!” All you said was, “More babies”.

You churned out nine children, all at different military bases. Germany, Japan, Kentucky, Washington, North Carolina, settling in San Diego. This sporadic geography invokes images of each of my aunts and uncles on their own little island.

[my dad is the only one in this photo not looking at the camera. I always thought that was funny]

You had the perfect reason, even beyond biological instinct, for repopulating. You had escaped death. It was time to pave over the past with a prosperity promised by the US government in exchange for your service, reeking of a boom, the 50’s in full swing.

Of course, we did not make the sacrifices you did to earn this metaphoric security you had, the principles that shaped your lives and personalities — but we are a product of it. We’ve been left with cryptic breadcrumbs — a striving for other people’s antiquated standards, a preoccupation with someone else’s ambiguous “American Dream”.

HEAVY~

There’s a fun war story on on my white side too - my great great grandparents died at the hands of the Bolsheviks in Russia; one by execution and one by suicide. At times it was crowded in my mind’s guilt zone. HEY! My ancestors shouted from all sides. YOU BETTER MAKE THIS WORTH IT! AND WTF IS THAT HAIRCUT?!

Blessed, everyone always said. We’re so blessed that we didn’t have to endure that! And of course we are. It was as if what you both endured was so horrible, that nothing could ever be painful again. It’s just that the story can’t end there, because people who don’t have to escape from wars are simply handed the detritus they cause.

For so many of us, stability, sobriety, higher education, and the upward social mobility of “American Dream” have been elusive. Is it our obsession with the narrative of what our family overcame that inhibits us from seeking help or naming how we’ve struggled? So reluctant to acknowledge mental health until forced to reckon with its decay?

Is the privilege of finding ourselves is so weighty and precious, that we can barely lift it?

SCIENCE & GOD~

Some scientific studies indicate that a previous generation’s trauma can alter not the way the descendants’ genes are built, but the way the genes are expressed. Not a fear of the stimulus itself, but a sensitivity to it.

The symptoms are literally inherited, received from an ancestor or predecessor from the past. It’s also likely that socialization is to blame. Perhaps it’s just a perfect blend of the two.

I cannot continue nor depend on that version of legacy. It’s a disservice to the absolute shit show you suffered to sit there and accept the emotional staleness that was given. We no longer need to put our grief into a box and think it won’t leak, tape it up with sugary holy language, and send it upward only to believe it won’t come down.

Praising god for surviving, for multiplying, feels so incomplete, suggesting that people who did not conceive, or the 70 million who died in WWII, did so because they forgot to thank someone.

It can’t be denied that religion is adequate or periodically helpful for people, but I’m suspicious of your theology being mapped onto situations or eras that theology is useless against. As Kate Winslet says in The Holiday, “very square peg, very round hole.”

Being misinterpreted, accused of being too sensitive/critical/entitled/leftist by people in this family is not scary to me anymore, so I will go ahead and honor you my way. By sifting through the rubble, both the innocuous and incendiary, by delving into our history unabashedly, by not minimizing the invisible pain you had to have felt and that I carry now.

Know thyself, says Socrates. Okay. I own our context, our history. Our persistence, our humor, and also our panic, rage, and dread. Our misconduct and guilt and hypocrisies, our violence and bitterness and death, our poverty, piousness, incarceration, indoctrination, our addiction and codependence, our neglect and resentments. No amount of praying can take them away. I’ll say to them go ahead and be here! Knock yourself out! Run in circles! Or they will crush me alive.

And if our family was together all the time, why couldn’t we ever do this together? How were we together so often, yet not at all?

When I’m in contact with my father, it has a tendency to feel as if I’m marinating in all of his pain. Like if he felt it himself, he would drown. Like I’m knocking on doors in an endless hallway, none of them opening. He told me once, frustrated, “You’re an enigma. I don’t understand why you’re the way you are.” But I do.

Miss you.

All my love,

Grandchild #12

🪐🪐🪐

NOTES~

ways generational trauma manifests in families

Share this post